Article · 6 minute read

By Amber Williams & Sarah Chan – 31st October 2024

Cognitive ability tests are among the most valid and widely used assessment methods for employee selection, but they are also known to show demographic group differences (e.g. Roth et al, 20011). These differences can lead to adverse impact, where the selection rate for minority ethnic groups is lower than that of White ethnic groups or majority groups; this has the potential to violate the 4/5ths rule; an indicator commonly used to check for the presence of adverse impact.

To increase fairness in cognitive testing, test publishers and organizations must take steps to ensure that no demographic group has an unfair advantage. This includes creating test content that minimizes bias, focusing on job-relevant aptitudes, and training users to administer and interpret tests fairly. These important steps are mainly concerned about the tests themselves and the use of tests. After careful design and implementation, is there anything else related to testing that can contribute to demographic group differences in test performance?

Our Research & Development team investigated whether the positioning of demographic collection during assessments affects test performance and fairness. This article explores those findings and suggests future considerations for candidate demographic data collection.

In addition to completing assessments, candidates are often asked to provide some personal information as part of their job application. They might be asked to give their gender, ethnic background, age group, education or qualifications. While qualifications may be important and required in some job applications, other personal information is usually not, and should not be used for decision making. However, the collection of such information is useful for the hiring organizations as well as test publishers.

Organizations can use demographic information to monitor the diversity of their applicant pools and evaluate the fairness of their selection processes. This insight allows them to adjust their candidate attraction strategies to be more inclusive and ensure that diversity, equity, and inclusion (DE&I) efforts are maintained over time. For test publishers, understanding the demographic composition of test takers helps develop norms that accurately reflect the intended population. It also supports ongoing monitoring of fairness in the tests and contributes to broader research initiatives aimed at improving assessment practices.

This is where it is useful to review research in social psychology, where the relationship between stereotype threat and test performance has been studied for decades.

Stereotype threat is when individuals feel at risk of conforming to negative stereotypes about their social group (Steele et al., 19952; Shih et al., 19993; Jamieson et al., 20114). Studies on stereotype threat demonstrate that individuals from minority ethnic groups that are primed – reminded of their group membership – subsequently underperformed on a test. Priming can activate negative societal stereotypes causing fear of fulfilling negative stereotypes. This fear may lead to negative thinking, anxiety and increased cognitive load, which can then affect performance; especially in high-stakes situations like exams, job assessments, or competitive tasks, and thus cognitive tests.

The effect of stereotype threat is not limited to ethnicity and applies to gender and any social groups which are assigned negative societal stereotypes. This research raises questions as to whether demographic group differences found in cognitive tests are partially impacted by stereotype priming – being asked to provide demographic data at the start of an assessment.

To research this issue, we moved the positioning of the demographic data collection on our assessment platform. Originally, the questions were presented to candidates when they first logged onto the assessment platform as a way to encourage them to fill in the information. Now the demographic information collection is shown as a separate task on the platform to encourage candidates to submit this after assessment completion.

To understand the impact of changing the demographic data collection position, our Research & Development team reviewed the data completion rates and test scores following the change.

An encouraging first result was that the new position did not reduce the completion rate but in fact increased it, from under 30% before, to around 70%. Candidates appeared to be more willing to fill in their information when it was a separate task for post-test completion.

In terms of the test scores, a large operational data set of over 130,000 completions on Swift Analysis Aptitude (a combination test that measures high level of verbal, numerical and logical reasoning) was analyzed.

The results indicated that moving the demographic data collection had less of an impact on test scores for male candidates or the White ethnic group – the average scores for these two groups remained very similar in the two demographic collection positions. In contrast, there were small improvements in the group average scores for both female candidates and candidates from minority ethnic groups. The differing trends for the majority groups (males, White ethnic group) and their counterparts (females, other ethnicities) mean that the gender difference as well as ethnic group difference on the test score are reduced in size.

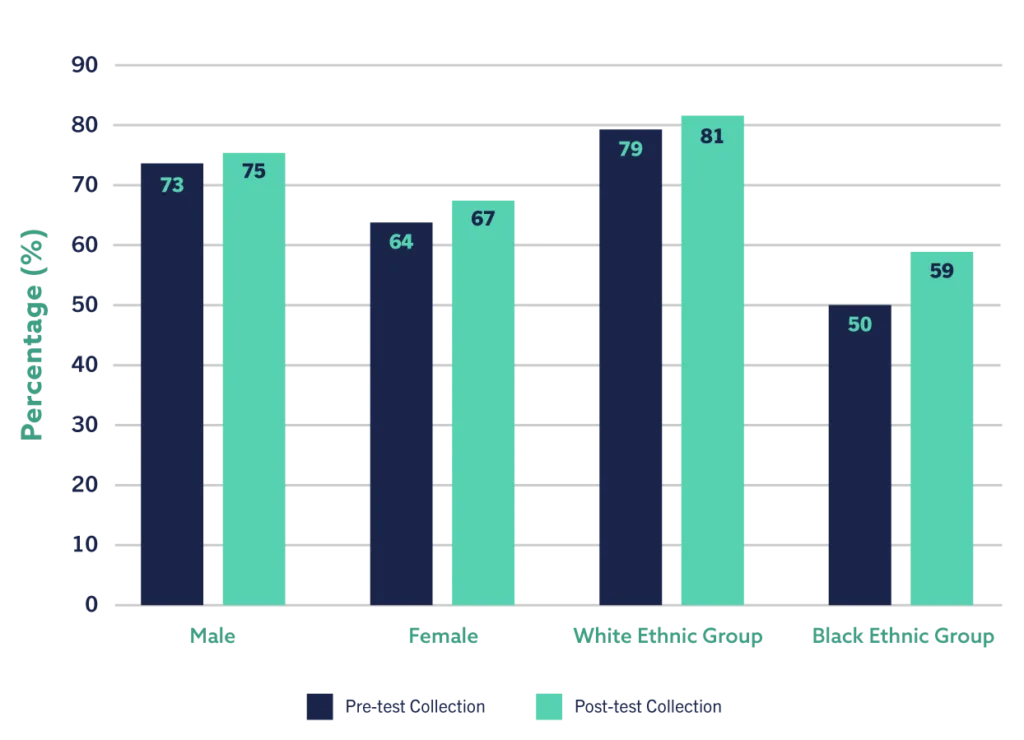

The graph below shows what this means in practical terms. As an example, when using our recommended cut-off score of 31st percentile (i.e. those who did not perform better than 31% of the comparison group would not be progressed to the next stage) a higher percentage of female and Black ethnic group candidates would ‘pass’ when demographic data collection is moved to post-test, compared to if they were more likely to complete the information before the test. The differences in the majority groups – males and White ethnic groups are less pronounced.

These results indicate that by simply changing the stage at which a candidate provides their demographic data in the assessment process can help reduce group differences in aptitude test scores. According to these results, it appears to benefit candidates overall, but particularly for those belonging to protected groups, i.e. females and minority ethnic groups. Therefore, removing the priming of stereotypes by not reminding candidates of their social groups before completing a test is in the right direction to increase test fairness. It is important to note that it is essential to recognize that stereotype threat can extend beyond aptitude testing so considerations must be made throughout the entire application process.

This article brings forward the concept of marginal gains—small, actionable steps that, together, create a fairer approach to selection and talent management. For example, as discussed above, simply addressing the role that stereotype threat can play in aptitude performance—even through making a small change in the collection of personal information—can be a meaningful first step. Other small yet impactful methods to reduce adverse impact include selecting validated tools that minimize group differences and combining assessments to significantly increase validity enabling fairer assessments—behavioral, aptitude, or SJTs (when in relation to Wave). By prioritizing these incremental changes, test publishers and organizations can build fairer practices that contribute to improved DE&I outcomes.

Our team will be happy to discuss this topic further with you and demonstrate other ways in which appropriate assessment usage can improve the fairness of a process. Get in touch to arrange a call or demo.

Amber is a Managing Consultant at Saville Assessment. She is a Neurodiversity at Work Expert and has a passion for creating inclusive assessments.

Sarah is a Senior Research Psychologist at Saville Assessment, managing our portfolio of aptitude tests.

You can connect with Sarah on LinkedIn here.

1Roth, P. L., Bevier, C. A., Bobko, P., Switzer, F. S. III, & Tyler, P. (2001). Ethnic group differences in cognitive ability in employment and educational settings: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 54(2), 297–330.

2Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 797–811.

3Shih, M., Pittinsky, T. L., & Ambady, N. (1999). Stereotype susceptibility: Identity salience and shifts in quantitative performance. Psychological Science, 10(1), 80–83.

4Jamieson, J. P., & Harkins, S. G. (2011). The intervening task method: Implications for measuring mediation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(5), 652–661.

5Smith, J., MacIver, R., Chan, S., (2024). Alternative Approaches to Maximizing Test Fairness. Symposium presented at the International Test Commission conference. Granada, Spain. 2024.

© 2024 Saville Assessment. All rights reserved.